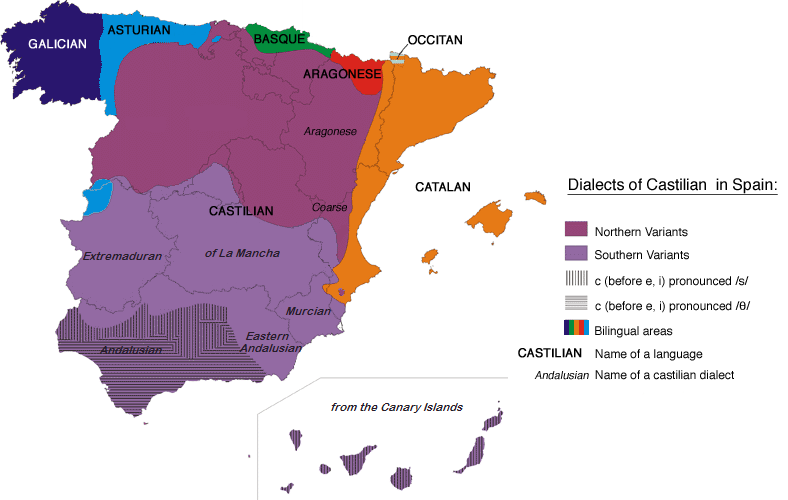

Did you know that they speak more than just Spanish in Spain? Did you know that there isn’t just one Spanish language, but perhaps eightSpanish languages? Until I started studying Spanish in college and came here for work, I had no idea myself. But it turns out that Spain is actually home to quite a few minority languages that make the country a very interesting place.

The post They Speak More Than Just Spanish in Spain appeared first on trevorhuxham.com

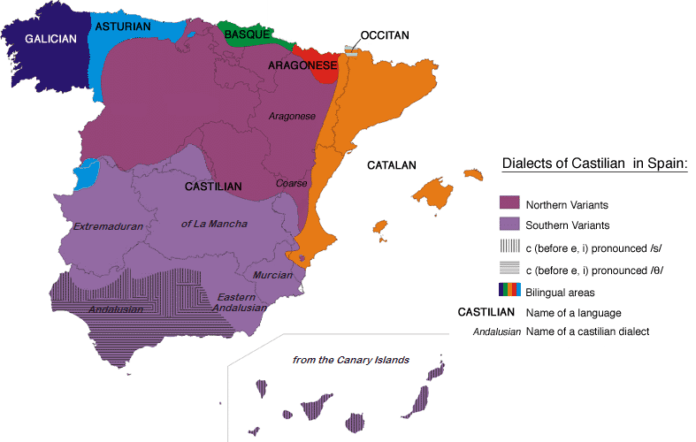

It makes a lot more sense that the birthplace of español could also be home to half a dozen other languages when you realize that Castilian Spanish began its life as the everyday Latin spoken around modern-day Burgos province in north-central Spain.

During the Reconquista—a 700-year military struggle by the fledgling Christian kingdoms to the north to “re”-conquer the Muslim-ruled (and Arabic-speaking) lands to the south—Castilian emerged alongside Galician, Astur-Leonese, Aragonese, and Catalan, and as the conquerors pushed south into the Moorish states, they brought their respective languages with them.

|

| (Source: Wikipedia) |

Under Alfonso X of Castilla & León (r. 1252-1284), however, Castilian Spanish began to gain the upper hand. Although Alfonso personally contributed a lot to medieval Galician poetry, it was he who first established Castilian as the official language of his courts, replacing Latin. Later on, western Castilla would join up with eastern Aragón when Ferdinand and Isabella got married in 1469, but the two realms remained distinct kingdoms with a single monarch.

After the 18th-century War of the Spanish Succession (a dynastic struggle/civil war), the new king Felipe V issued the Nueva Planta decrees that made Castilian laws universal throughout the country and Castilian the language of government. He did this partly to centralize Spain and partly to punish the regions of Aragón, Cataluña, and Valencia, which had opposed him in the war (and which also spoke Aragonese and Catalan).

The last major threat to Spain’s minority languages came during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, who led the conservative Nationalists to victory in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Although he himself was born in Galicia, his ideology of conformity (called National Catholicism) mandated Castilian Spanish as the sole official language of the state; it became a crime to speak Galician in public, for example.

|

| (Source: Wikipedia) |

However, after Franco died and King Juan Carlos I initiated la Transición to liberal democracy, the new constitution enshrined protections for minority languages, four of which are now co-official in their respective regions. Today, once critically-endangered languages are making a comeback and Galician, Basque, and Catalan are stronger than ever before in recent history.

In this post I would like to introduce eight Spanish languages other than what we typically think of as “Spanish.”

Galician

Astur-Leonese

Basque

Aragonese

Aranese (Occitan)

Catalan

Gomeran whistle

Example recording:

Iberian Romani

Native name: caló

Number of speakers: 40,000

Description and status: Spoken almost exclusively by Spain’s Gypsy population (a.k.a. the Romani people), the caló language is actually a “mixed” language that takes Spanish grammar and replaces most Spanish words with a totally different lexicon. Remember that modern-day Gypsies are descendants of nomadic people from northern India who migrated to Europe centuries ago; hence, Iberian Romani takes a lot of its vocabulary from the ancestral spoken language but operates using Spanish grammatical rules.

I actually encountered el caló at my school last year: I was in a second-grade bilingual science class talking about words for food in English when the teacher asked one of the Gypsy boys what the word for “oil” was in his language, and he replied with the word “ampio.” So cool!

Example text:

Y sasta se hubiese catanado sueti baribustri, baribustri, y abillasen solictos á ó de los fores, os penó por parabola: Manu chaló abri á chibar desqueri simiente: y al chibarle, yeque aricata peró sunparal al drun, y sinaba hollada, y la jamáron as patrias e Charos. Y aver peró opré bar: y pur se ardiñó, se secó presas na terelaba humedad. Y aver peró andré jarres, y as jarres, sos ardiñáron sat siró, la mulabáron. Y aver peró andré pu lachi: y ardiñó, y diñó mibao á ciento por yeque. Penado ocono, se chibó á penar á goles: Coin terela canes de junelar, junele. — “Parable of the Sower” (Luke 8:4-8)